Category: History

“Contrology by Joseph Pilates” by Rael Isacowitz

ROMANA KRYZANOWSKA 1923-2013

by Marjolein van Sonsbeek

Romana Kryzanowska was born into a very artistic family on June 30th 1923, in a town near Detroit. She always remained the only child in the family. Without a doubt Romana was the one who remained most loyal of all Elders to Joseph and Clara Pilates. Unfortunately Romana died not too long ago in her sleep, on August 30th 2013. Her death is a big loss to the Pilates community.

Faithfull to Joe’s method

Faithfull to Joe’s method

In my opinion; there wouldn’t be traditional Pilates in the Netherlands without Romana Kryzanowska. Maybe something would exist that would resemble it, but I don’t think Contrology would exist. Joseph Pilates initially called his method Contrology and that original heritage is what Romana taught the world. She never stopped to pass on Joseph’s original version. She has never deviated from the original and has always remained true to what Joseph has taught her since 1942.

Joseph’s biggest fan

Joseph’s biggest fan

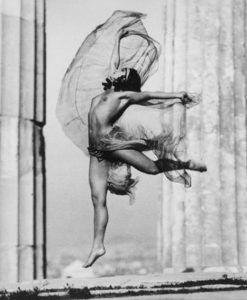

In 1942 Romana came to Joseph’s Pilates studio for the first time. That same year she got accepted as a dancer to The School of American Ballet; George Balanchine’s school. Due to track, Romana was unable to dance anymore. She was 19 years old at that time. After some visits to doctors who couldn’t help her, George Balanchine (a client of Joseph himself) took her to Joseph’s Contrology-Art-Studio-Pilates of Joseph Pilates. When she got there, she was ordered not to dance for at least two weeks, and do the assignments Joe had given her instead. She later told her mom she hated the studio. It was an old, dark building and the studio reeked of sweat. She also thought it was odd that this weird, surly and intimidating man had barely looked at her foot. She didn’t want to go back, but her mom made her. But, in no time Romana changed her mind. Not only did her ankle and foot heal, her dancing had improved and so had her stamina. She became Joseph’s biggest fan.

Follow in Joseph’s tracks

Follow in Joseph’s tracks

Romana continued to come to the studio as often as she could next to her dance practice, sometimes even twice a day! She mostly worked on the machines, because matclasses were mostly taught to clients that often travelled. She learned all Contrology- techniques and after a year Romana became an assistant and taught classes herself. She did not get paid for her services, but she got the knowledge about the method.

When Romana was 21 she married a wealthy businessman from Peru; Pablo Meija. They decided to move to Peru, which saddened not only Romana’s mother, but Joseph and Clara too. She had became a good friend to them, and also indispensable to their studio. Romana and Pablo had 2 children; Paul and Sari. She always kept in touch with Joseph and Clara, and in 1958 Romana returned to America and started teaching in Joe’s studio again. At that time Joseph and Clara had gotten pretty old, but they still worked in their studio every day. Their friendship became even closer and she called them “Uncle Joe” and “Aunt Clara”. Together with John Winters Romana started managing the studio. In her copy of “Return to life through Contrology”*, Joseph wrote that Romana was to be the one to step in his tracks.

Romana kept the studio running

Romana kept the studio running

Romana kept working and studying in the studio until Joseph died in 1967. Clara and Romana kept the studio running and in 1970 Romana became the manager of ‘The Pilates Studio’, which was the name of the studio at that time.

After Clara died in 1977 Romana kept working in the studio in New York together with her daughter; Sari. They later founded Romana’s Pilates and travelled all over the world to teach other trainers about true Contrology.

Full commitment

Romana closely watched the level at which exercises were performed. She was very strict. She wouldn’t accept her students doing their exercises halfheartedly. She demanded full dedication, but her sense of humor and her “every day is a party”- attitude made her a well- loved person. A few trainers even lived with her, where they were able to train with her intensively. Romana continued – even until she was very old – to demonstrate the pure Pilatesmethod all around the world; she demonstrated advanced exercises on the Cadillac with ease until she was 80.

She often came to Marjorie Oron’s studio on The Hague to teach Pilates. Her daughter Sari Meija Santo is now in charge to teach Joseph’s heritage to the world.

It later became apparent that Joseph started a few myths. She never thought it was true that he had been untrue about his age and other things. Javier Pèrez Pont and Esperanza Aparicio Romero wrote the biography about Joseph Pilates – The Biography; Joseph Hubertus Pilates – at her request. For years she relentlessly asked them to write this book about her hero and this resulted in a bulky and complete work about the life of this genius. The authors, Javier and Esperanza, frequently passed on what they had found out about Joseph’s life to Romana. Romana just couldn’t believe, even though this was proven by clear facts and documents, that Joseph had not always told the truth.

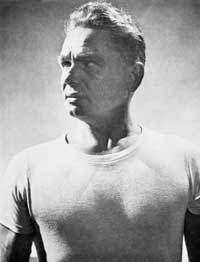

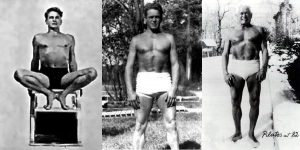

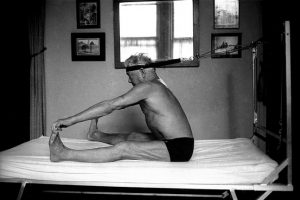

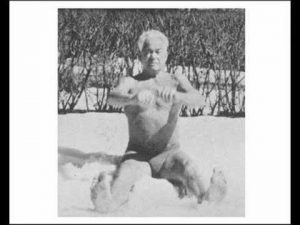

Joseph Pilates 1880 – 1967

(physical trainer, was born near Düsseldorf, Germany. His exact date of birth and the full names of his parents are unknown. His father, a champion gymnast, was Greek; his mother, who was German, worked as a naturopath. The family name, of Greek origin, is pronounced “Puh-lah-tees” and was derived from its original version, Pilatu. As a child, Joseph Pilates suffered from a variety of ailments, including asthma, rickets, and rheumatic fever, and was bullied by other boys who made fun of his name, calling him “Pontius Pilate, killer of Christ.” Determined to improve his spindly physique as well as his self-esteem, he became obsessed with bodybuilding, gymnastics, and the practice of yoga. (physical trainer, was born near Düsseldorf, Germany. His exact date of birth and the full names of his parents are unknown. His father, a champion gymnast, was Greek; his mother, who was German, worked as a naturopath. The family name, of Greek origin, is pronounced “Puh-lah-tees” and was derived from its original version, Pilatu. As a child, Joseph Pilates suffered from a variety of ailments, including asthma, rickets, and rheumatic fever, and was bullied by other boys who made fun of his name, calling him “Pontius Pilate, killer of Christ.” Determined to improve his spindly physique as well as his self-esteem, he became obsessed with bodybuilding, gymnastics, and the practice of yoga.  By the age of fourteen he had become so physically fit that he was hired to pose for anatomical charts. Pilates attributed the dramatic turnaround in both his health and his physical appearance to proper breathing techniques and correct posture, and he devised a series of exercises to maintain the well-being he had fought so hard to gain. By the age of fourteen he had become so physically fit that he was hired to pose for anatomical charts. Pilates attributed the dramatic turnaround in both his health and his physical appearance to proper breathing techniques and correct posture, and he devised a series of exercises to maintain the well-being he had fought so hard to gain.

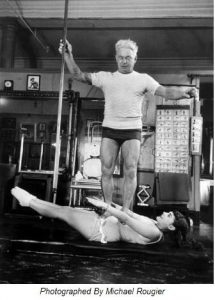

Working in partnership with his wife, Pilates opened a gym, which he referred to as his “studio,” at 939 Eighth Avenue, on the city’s West Side. The neighborhood also had several dance studios, and soon he was attracting a clientele that included ballet company members as well as actors and athletes. As word spread of his teachings’ effectiveness, laypersons seeking to improve their physical well-being also enrolled in his classes, prompted by a growing popular interest in so-called “physical culture” during the 1920s. Over the years Pilates trained some of his students to become teachers of his method; those who adhered strictly to his teachings became known as the “Pilates Elders” and practiced what became known as “Classical Pilates.” Other Pilates-trained teachers refined and altered his techniques to their own liking, incorporating elements of other fitness disciplines.

In private life Pilates was known as a gregarious party lover who nevertheless managed his diet carefully. His only weakness was a lifelong addiction to cigar smoking, which is believed to have caused an ultimately fatal case of emphysema; he died in a New York hospital. Clara Pilates continued to run the West Side studio for ten years, and Pilates-trained practitioners carried his teachings to other centers throughout the country. The method remained a largely exclusive practice, followed by dance and acting professionals, top-flight athletes, and socialites, until the 1990s, when it began attracting a wider following among the general public–specifically so-called “baby-boomers,” persons born during the postwar years who were now entering middle age and becoming increasingly fitness-conscious. The Pilates craze that ensued had been predicted by Pilates himself, who often expressed the belief that he was fifty years ahead of his time. As of 2008 there were Pilates studios throughout the world, more than five hundred in the United States alone, and celebrities and unknowns alike attested to the method’s usefulness in strengthening and slimming their bodies. |

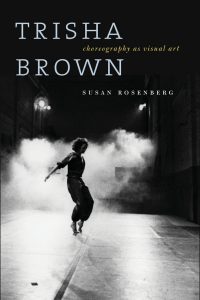

Trisha Brown 1936-2017

Excerpt from the book “Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art” by Susan Rosenberg

It is with great sorrow that we share the news that artist Trisha Brown (b. 1936) died on March 18th in San Antonio, Texas, after a lengthy illness. She is survived by her son, Adam Brown, his wife Erin, her four grandchildren and by her brother Gordon Brown and sister Louisa Brown. Trisha Browns husband, artist Burt Barr, died on November 7, 2016.

It is with great sorrow that we share the news that artist Trisha Brown (b. 1936) died on March 18th in San Antonio, Texas, after a lengthy illness. She is survived by her son, Adam Brown, his wife Erin, her four grandchildren and by her brother Gordon Brown and sister Louisa Brown. Trisha Browns husband, artist Burt Barr, died on November 7, 2016.

One of the most acclaimed and influential choreographers and dancers of her time, Trishas groundbreaking work forever changed the landscape of art. From her roots in rural Aberdeen, Washington, her birthplace, Brown a 1958 graduate of Mills College Dance Department arrived in New York in 1961. A student of Anna Halprin, Brown participated in the choreographic composition workshops taught by Robert Dunn from which Judson Dance Theater was born greatly contributing to the fervent of interdisciplinary creativity that defined 1960s New York. Expanding the physical behaviors that qualified as dance, she discovered the extraordinary in the everyday, and brought tasks, rulegames, natural movement and improvisation into the making of choreography.

With the founding of the Trisha Brown Dance Company in 1970, Brown set off on her own distinctive path of artistic investigation and ceaseless experimentation, which extended for forty years. The creator of over 100 choreographies, six operas, and a graphic artist, whose drawings have earned recognition in numerous museum exhibitions and collections, Browns earliest works took impetus from the cityscape of downtown SoHo, where she was a pioneering settler. In the 1970s, as Brown strove to invent an original abstract movement language one of her singular achievements it was art galleries, museums and international exhibitions that provided her work its most important presentation context. Indeed contemporary projects to introduce choreography to the museum setting are unthinkable apart from the exemplary model that Brown established.

Browns movement vocabulary, and the new methods that she and her dancers adopted to train their bodies, remain one of her most pervasively impactful legacies within international dance practice. However for Brown, these techniques were a means to an end the creation of choreographies, which unfolded in a serial fashion. In the Equipment Dances (1968-1971), she explored gravity, perception and urban space. Brown introduced new rigor and systematicity to the Accumulations (1971-1975), dances derived from mathematical sequences common to the work of minimal and conceptual artists of her generation. When Brown developed what she named memorized improvisation she discovered the foundational approach that would inform her dance-making for the remainder of her career. First announced in her solo Watermotor (1978) a dance immortalized in the film shot by Babette Mangolte Browns extraordinary, idiosyncratic virtuosity as a dancer became the touchstone for her mature movement vocabulary. It also served to demonstrate that, among the many components of Browns genius, was her ability to forge, access and represent the inseparability of mind-body intelligences.

Working in the studio with what was, until 1980, an all-female company, Brown became a master orchestrator of collaboration; she used her own body, language and images to elicit and catalyze her dancers improvisations, which she edited and structured as choreographies. A major turning point in Browns career occurred in 1979, when she transitioned from working in non-traditional and art world settings to assume the role of a choreographer working within the institutional framework associated with dancing the proscenium stage.

With this decision she embarked on a more expansive collaborative process, inviting her contemporaries to contribute visual presentations (sets and costumes) as well as sound scores to her choreography. In her initial work with Robert Rauschenberg on Glacial Decoy (1979) she established the parameters for their artistic dialogue at the outset, drawing inspiration from the theaters geometry and sightlines. Going forward, in her work with artists Fujiko Nakaya, Donald Judd, Nancy Graves, Terry Winters and Elizabeth Murray, and composers Robert Ashley, Laurie Anderson, Peter Zummo, Alvin Curran, Salvatore Sciarrino, and Dave Douglas, Brown identified the collaborative process as a manifestation of interacting and intersecting artistic intentions and she worked hand in glove with these artists to bring each new production to fruition.

Browns best-loved work, the 1983 Set and Reset a collaboration with Robert Rauschenberg and Laurie Anderson that premiered as part of the Brooklyn Academy of Musics Next Wave Festival brought Brown international fame. It culminated the group of dances known as the Unstable Molecular Cycle, (1980-1983), all based in memorized improvisation. In The Valiant Cycle (1987-1989) Brown pushed the limits of her dancers athleticism and stamina, elevating abstract dance to theatrical proportions in her masterpiece, Newark (Niweweorce) (1987) for which Donald Judd provided the sets, costumes and sound score. With the Back to Zero Cycle (1990-1994) Brown entered new terrain, investigating unconscious movement, while also bringing new inflections to her longstanding concern with themes of visibility and invisibility, as well as visual deflection.

Having performed in Lina Wertmullers 1987 production of Bizets Carmen, Brown in the mid-1990s set her sights on directing operas. In preparation she initiated the Music Cycle, in which she collaborated with what she described as two dead i.e. timelessly alive composers: Johann Sebastian Bach and Anton Webern. With new knowledge of polyphonic musical forms, she accepted the invitation of Bernard Foccroulle, director of Brussels famed La Monnaie opera house, to direct Monteverdis LOrfeo in 1998 the first of six operas that she would direct over the next fourteen years. In addition to engaging with this most venerable of interdisciplinary art forms, Brown created a single ballet, O Zlozony/O Composite (2004), at the behest of Brigitte Lefλvre, director of The Paris Opera Ballet a project in which she worked with three of the companys most esteemed Ιtoiles, and with artist Vija Celmins and composer Laurie Anderson. During the late 1990s and first decade of the 21st century, Brown worked simultaneously to create new choreographies working with contemporary artists and composers; directed operas; and further developed her work in the field of drawing.

Browns official retirement from dancing came in 2008, when she performed in I Love My Robots, a collaboration with Kenjiro Okazaki and Laurie Anderson. Her final works include two operas by Jean-Philippe Rameau, Hippolyte et Aracie and Pygmalian (2010), produced together with William Chrystie and Les Arts Florissants as well as the sole male duet that she created, entitled Rogues (2011). Her work, Im going to toss my arms- if you catch them theyre yours (2011), was the last dance Brown created. From the 1970s to the present Trisha Browns drawings have been widely exhibited in international museums and art galleries among them, at Yale University Art Gallery and the Leo Castelli Gallery (1974); the Venice Biennale (1980); The Fabric Workshop & Museum, Philadelphia (2003); White Box Gallery, London (2004); Documenta XII (2007); and The Walker Art Center (2008). In addition, her drawings are held in major museum collections, including the Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, The Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris among others. Brown is represented by Sikkema Jenkins & Co. in New York.

Today the Trisha Brown Dance Company continues to perpetuate Browns legacy through its Trisha Brown: In Plain Site initiative. Through it, the Company draws on Browns model for reinvigorating her choreography through its re-siting in relation to new contexts that include outdoor sites, and museum settings and collections. The Company is also involved in an ongoing process of reconstructing and remounting major works that Brown created for the proscenium stage between 1979 and 2011. In addition, the Company continues its work to consolidate Trisha Browns artistic legacy through their restoration and organization of her vast archives of notebooks; correspondence; critical reviews; and an unprecedented moving image catalogue raisonnι, which records her meticulous creative process over many decades.

In her lifetime Trisha Brown was the recipient of nearly every award available to contemporary choreographers. The first woman to receive the coveted MacArthur Genius Grant (in 1991), Brown was honored by five fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts; two John Simon Guggenheim Fellowships; and Brandeis Universitys Creative Arts Medal in Dance (1982). In 1988, she was named Chevalier dans lOrdre des Arts et Lettres by the government of France. In January 2000, she was promoted to Officier and in 2004, she was again elevated, this time to the level of Commandeur. Brown was a 1994 recipient of the Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award and, at the invitation of President Bill Clinton, served on the National Council on the Arts from 1994 to 1997. In 1999, she received the New York State Governors Arts Award and, in 2003, was honored with the National Medal of Arts. She received the Capezio Ballet Makers Dance Foundation Award in 2010 and had the prestigious honor to serve as a Rolex Arts Initiative Mentor for 2010-11. She has received numerous honorary doctorates, is an Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and was awarded the 2011 New York Dance and Performance Bessie Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2011, Brown received the prestigious Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize for making an outstanding contribution to the beauty of the world and to mankinds enjoyment and understanding of life. In 2012, Brown became a United States Artists Simon Fellow. Having received three awards from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts (1971, 1974, and 1991), she was honored with the Foundations first Robert Rauschenberg Award in 2013. In 2013 she was honored with the BOMB Magazine Award and received the Honors Award given by Dance/USA in 2015. ~ Susan Rosenberg

As a young man Pilates variously earned a living as a self-defense trainer, a boxer, and a circus performer in Germany and later in England, where he emigrated in 1912. Two years later, following the outbreak of World War I, he was classified as an enemy alien by the British government and was sent with other German nationals to the Isle of Man, in the Irish Sea. He was interned there for the duration of the war. To pass the time, he began teaching fitness exercises to other inmates. He devised special programs for those who were bedridden and created makeshift devices for strength training.

As a young man Pilates variously earned a living as a self-defense trainer, a boxer, and a circus performer in Germany and later in England, where he emigrated in 1912. Two years later, following the outbreak of World War I, he was classified as an enemy alien by the British government and was sent with other German nationals to the Isle of Man, in the Irish Sea. He was interned there for the duration of the war. To pass the time, he began teaching fitness exercises to other inmates. He devised special programs for those who were bedridden and created makeshift devices for strength training. Following his release at the war’s end in 1918, Pilates returned to Germany to work as a fitness trainer in Hamburg. The routines and machinery that he fashioned on the Isle of Man became the basis for what became known as the Pilates Method, the fitness program that he began to develop and refine during the postwar years. Word of his success with individual clients spread, and he was hired by the city of Hamburg to train its policemen. His techniques were also adopted by the German army. However, worsening economic conditions in Germany prompted Pilates to consider emigration yet again, and in 1925 he sailed for the United States. On board the ship he met a woman named Clara, who shared his interest in physical fitness. A romance developed, and they were married soon after their arrival in New York City.

Following his release at the war’s end in 1918, Pilates returned to Germany to work as a fitness trainer in Hamburg. The routines and machinery that he fashioned on the Isle of Man became the basis for what became known as the Pilates Method, the fitness program that he began to develop and refine during the postwar years. Word of his success with individual clients spread, and he was hired by the city of Hamburg to train its policemen. His techniques were also adopted by the German army. However, worsening economic conditions in Germany prompted Pilates to consider emigration yet again, and in 1925 he sailed for the United States. On board the ship he met a woman named Clara, who shared his interest in physical fitness. A romance developed, and they were married soon after their arrival in New York City. The Pilates Method–in its early years it was called Contrology–was grounded in a series of exercises that called for stretching, pulling, and contracting parts of the body to strengthen muscles in the abdomen and pelvic area and to foster proper spinal alignment, while simultaneously practicing rhythmic breathing. Some of the exercises, which had such names as the Corkscrew, Hot Potato, and Can Can, were done on the floor; others, such as the Cadillac, the Barrel, and the Reformer, involved the use of simple machines that Pilates designed. The Pilates Method was demanding and the training was expensive, which meant that devotees had to be committed to its practice. Pilates’s students thus formed a rather exclusive club that over the years included the celebrated dancers and choreographers

The Pilates Method–in its early years it was called Contrology–was grounded in a series of exercises that called for stretching, pulling, and contracting parts of the body to strengthen muscles in the abdomen and pelvic area and to foster proper spinal alignment, while simultaneously practicing rhythmic breathing. Some of the exercises, which had such names as the Corkscrew, Hot Potato, and Can Can, were done on the floor; others, such as the Cadillac, the Barrel, and the Reformer, involved the use of simple machines that Pilates designed. The Pilates Method was demanding and the training was expensive, which meant that devotees had to be committed to its practice. Pilates’s students thus formed a rather exclusive club that over the years included the celebrated dancers and choreographers  Pilates wrote several books about his method, including Your Health: A Corrective System of Exercising that Revolutionizes the Entire Field of Physical Education (1934) and Return to Life Through Contrology (1945; repr. 2005), the latter coauthored with William John Miller. He also patented more than two dozen exercise devices.

Pilates wrote several books about his method, including Your Health: A Corrective System of Exercising that Revolutionizes the Entire Field of Physical Education (1934) and Return to Life Through Contrology (1945; repr. 2005), the latter coauthored with William John Miller. He also patented more than two dozen exercise devices.